1901 Steinway Model B

1901 Steinway Model B

1901 Steinway B for Sarah Hershey Eddy SOLD

Piedmont Piano Company is pleased to offer for sale, for the first time since it was purchased new from Steinway & Sons in New York in 1901, this unique and stunning Steinway model B grand piano in a figured mahogany case hand painted for its original owner, Sarah Hershey Eddy, by noted artist Arthur E. Blackmore.

The piano survives in astonishing original condition, never having been restored but beautifully preserved both inside and out - a stunning work of decorative art but also a fine musical instrument ready to serve the most discriminating pianist.

Equally remarkable to the piano’s rarity, beauty and condition is the story of its life in the ownership of five generations of its original family, a history of remarkable women and elaborate mansions in France and Hollywood, with the piano ultimately arriving in Berkeley CA where it has remained for the last seven decades - with its early history meticulously preserved in family documents and photographs.

Size 6ft. 11in. Serial number 98493.

ORIGINAL OWNER - SARAH HERSHEY EDDY

The original owner of Steinway B #98493 was Sarah Hershey Eddy, a very prominent figure in music and music education in America in the 19th century. Mrs. Eddy was born Sarah Hershey in 1837 in Pennsylvania, a distant relative of Milton S. Hershey, founder of the famous chocolate company. Her father Benjamin Hershey made an enormous fortune in lumber and Sarah began her music studies as a young girl. By the time she was 20 she was living in Muscatine, Iowa where her father had moved the headquarters of his lumber and farming businesses. It is worth noting here that Sarah married William F. Brannan of Muscatine in 1857, because although that union lasted only a short time, it produced in 1861 her daughter Elizabeth McLeod Brannan, who decades later would become the Steinway piano’s second owner.

By the time her daughter had reached the age of six, Sarah was pursuing the finest musical education money could buy in the musical capitals of Europe. It’s unclear whether her young daughter was in tow or back in the US being raised by relatives, but Sarah Hershey was studying voice with the vocal masters of Europe; first in Berlin, and later in Milan and London. She became an accomplished singer and this piece describing her appeared (with perhaps a degree of hyperbole) in a “United States Biographical Dictionary” in the 1870s:

She studied under the best maestros in London, Berlin and Milan for five years and is now perhaps the most perfect mistress of harmony in the United States. She is also an accomplished linguist speaking the German, Italian, and French languages only less fluently than the English. Nor is she less cultured in the fine arts, to which she also gave much attention; her extensive study and travel having made her quite a critic in sculpture and painting. She is, withal, a queenly woman; majestic in appearance, graceful and elegant and all her motions, and peerless in every noble and amiable quality. She has recently appeared in operas in New York, London and several cities of the continent of Europe where she has been regarded as a “star” of the first magnitude and is destined to a career of fame and success second to no artist of the century.

Despite this glowing description of her artistic talents, Sarah did not pursue a career in performance, but was much committed to the cause of music education. In 1871 she was in New York performing occasionally but teaching regularly. The same year she was named head of the music department at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, collecting the highest salary, to that date, paid to a woman in the state of Pennsylvania.

By 1875 she had moved to Chicago, and with the help of her father’s fortunes she founded the Hershey School of Musical Art, which within a few years became a highly respected music institution, providing education in vocal arts, composition and particularly organ after the arrival in 1876 of director Clarence Eddy, one of the world’s most acclaimed organists who had performed throughout Europe and the United States. In those halls of musical academia love bloomed, and although Clarence was fourteen years younger than Sarah they were married in 1879.

Within six years, however, Mr. and Mrs. Eddy had both left the Hershey School, as noted in “the Voice”, a national vocal arts publication:

“…the responsibilities of such an institution however, became too arduous, and in 1885 both Mr. and Mrs. Eddy retired to private teaching, with a large following of pupils. The artist couple lead an ideal life of artistic and domestic companionship. Their apartments, charged with musical life and culture, are charmingly located, commanding a view of Lake Michigan.”

During these years Mrs. Eddy became very active as a writer for prominent musical publications as well as an advocate for music education. She was a prominent figure in the Music Teachers’ National Association, the American College of Musicians, and the Women’s Musical Congress at the 1893 Worlds fair in Chicago.

But things were about to change. In 1893 Sarah’s father Benjamin Hershey died and left her an enormous fortune. Two years later she retired completely from the music world and she and Clarence moved to Paris, to a substantial home on the fashionable rue de Faisanderie. Once settled in she became a well known hostess for the local music community and Americans visiting Paris, and her home was the scene of many soirees and musicales.

As the 20th Century dawned, Sarah Hershey Eddy, now in her mid sixties and a resident of France, ordered a very special Steinway grand piano, and began planning its new home - a great riverside mansion dedicated to music.

THE PIANO

Steinway & Sons records indicate that the model B grand bearing the serial number 98493 was “released from the factory” on February 26, 1901. The only other Steinway factory notation is that the piano was “painted by Blackmore”, but because of the careful preservation of original records by Mrs. Eddy’s descendants, we have considerably more information about the beginning of the piano’s life. The wonderfully preserved original sales receipt from Steinway, made out in the name of Mrs. Clarence Eddy, is dated over a full year later on April 5th 1902. And written between between these dates, on November 16 1901, is a hand written letter from the artist Arthur E. Blackmore, who created the paintings that decorate the mahogany case. This indicates the piano was almost certainly custom ordered Mrs. Eddy, and finished and decorated over the course of 1901 and early 1902.

The letter from Mr. Blackmore indicates the importance of this piano, and its decoration, to Steinway & Sons: its recipient, “Mr. N. Stetson”, would be Nahum Stetson, Steinway’s vice president, Chief of Sales, and member of its Board of Directors. In response to a question from Mr. Stetson, Blackmore is replying about the inspiration for the decoration of the piano: the quotation I used on Mrs. Eddy’s piano viz. “so love was crowned, but music won the cause” you will find it the 5th stanza of - Alecsander (sic) Feast - or the power of music - a song in honor of St. Cecilia’s Day written by John Dryden 1697. The Stanza concludes “at length with love and wine oppressed the vanquished victor sank upon her breast”.

This is a fascinating peek into the style and inspiration of artists and their patrons at the turn of the 20th Century. Alexander’s Feast by Dryden (1631-1700) is a lengthy ode concerning a feast given by Alexander the Great, and the beauty and power of music, and perhaps was given to Blackmore by Mrs. Eddy to use as the basis for the floral and musical themed paintings that adorn the piano.

Arthur E. Blackmore

Arthure E. Blackmore (1854-1921) was one of the talented artisans employed in the Steinway Art Depatment at the turn of the century. He was employed as a Steinway artist for twenty years before succeeding J.Burr Tiffany, of the renowned Tiffany family of New York, as head of the art department at Steinway in 1913. Blackmore embellished only a small number of Steinway pianos, some of which are now on display at museums around the United States. In 1905 the publication The Collector and Art Critic reported on a visit to his workshop:

On a visit to his studio in the Steinway building, I was delighted with the examples on which he happened to be engaged. Mr. Blackmore seems to be possessed with a wonderful natural aptitude in verve, fantasy, grace and fertility of invention. Nor does he slur, for, as demanded by the peculiar insistency of his craft, he paints his figures freed from all material grossness in delicate finesse. His graceful groups and charming attitudes refer to a race of a dreamed universe, a fairy land of calm, of peace, of gentle passions and of laughter sweet, where spring reigns eternal and the trees are green forever… The Steinway Company may surely be congratulated in having the inventive genius of this meritorious painter at their service.

The Case: The basis for the piano case is the variation Steinway referred to at the time as the “new arm style” indicating the scroll carving of the front corners of the case flanking the keyboard. The music desk is of the elegant design that was standard on the new arm pianos, with carvings around the edges that compliment the carvings on the arms. The legs and pedal lyre, however, are not standard Steinway issue and look to have been custom made, and we have never seen others like them. The legs are massive, square and tapered with gilded channels extending downward from heavily carved capitals and ending in stylized “lion” feet. With the matching lyre the piano has a more substantial look then the standard cases of the era - an appearance of great solidity.

All the upper case components are veneered in an exceptional figured flame grain mahogany with a remarkable shimmering caste - most certainly a specially selected wood. All of the moldings are painted in gold, many with elaborate repeating designs. The music desk, key cover, sides and lid are decorated by the hand paintings of Mr. Blackmore featuring fairies and nymphs, musicians, and extensive floral decorations. Most painted pianos we have seen in this period feature opaque painted backgrounds but here the hand painting directly on the finished exotic wood creates a stunning combination.

CONDITION: As stated above, the piano survives today in an original, unmolested unrestored condition that can only be described as astounding. Both inside and out every component is as it came from the factory - with the original strings, soundboard, bridges, hammers, action components and ivory keys in extremely fine condition. Equally fine is the condition of the decorated mahogany case, with the original varnished and painted surfaces showing only a minimal (and quite attractive, in our opinion) patina of age. Five years ago the piano was inspected by a prominent Steinway specialist (not associated with our business) who wrote these comments: “It is in astonishingly fine condition as both a musical instrument and a piece of furniture…The exterior finish is in excellent condition.The ivory and ebony keyboard is in virtual(ly) like-new condition. The soundboard and bridges are in excellent condition and the crown and tone quality are exceptional… It would be virtually impossible to reproduce an instrument of this caliber today. This is undoubtedly one of the finest and best preserved Steinways I have had the pleasure of seeing in over 30 years of experience.”

From a performance standpoint the piano is a very fine instrument - with an extremely even touch and the gorgeous deep tone that is heard only in the finest Steinways, whether they have been restored or not! Our friends from the midwestern and eastern states in the US may raise an eyebrow hearing about a 115-plus year old piano that is unrestored and still sounds fabulous, as this is unheard of in those climate challenged areas. But this piano is the living proof that instruments survive exceptionally well in the friendly California climate (the piano came to CA early in its life, as detailed below) and even at this advanced age can have decades of useful life ahead of them.

When Mrs. Eddy chose her Steinway model B in 1901, she was choosing the model that was then, as now, considered a “musician’s piano”, its seven foot size giving it a rich bass sound and the power of tone necessary to fill a large room. And Mrs. Eddy’s model B was destined to live in some very large rooms.

THE FIRST HOME: MANOIR DENOUVAL

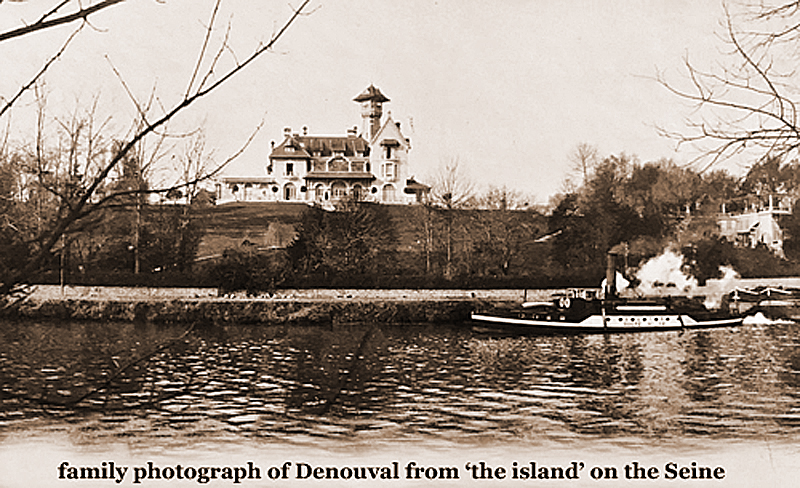

While the piano was under construction in New York Sarah Hershey Eddy was making larger construction plans in France. Having established herself as a leading figure in the American arts community in Paris, Mrs. Eddy was busy planning the construction of a great manor house at Andrésy, about 35 miles to the northwest of Paris, where she had acquired a large plot of land on the river Seine. The house was to be the centerpiece of an massive estate on the banks of the river surrounded by acres of farmland and gardens. Designed by prominent architect Pierre Sardou and given the name Manoir Denouval, the huge mansion’s prominent features were a tall tower and an enormous music “hall” where the new Steinway would sit at the foot of a massive pipe organ built by Cavaillé-Coll, France’s greatest organ builder.

The great manor house was begun in 1904 and was under construction for four years, and in 1908 the organ and the beautifully decorated Steinway piano were installed. But surprisingly, before the work was completed the 26-year marriage between Sarah and Clarence ended, with Clarence filing for divorce in 1905, citing desertion. It’s likely he never played the magnificent organ and when the manoir was dedicated on June 21, 1908, an inaugural organ recital was presented not by Clarence Eddy, but rather famed French organist Alexandre Guilmant. This well publicized social event was attended by prominent artists and composers including noted playwright Victorien Sardou (the architect’s father) and composer Camille Saint-Seans.

Most interestingly, just five days later, Sarah, now 71 years of age, married her third and last husband, an Englishman thirty five years her junior by the name of John Darlington Marsh. Mr. Marsh had something of a checkered background and it’s not clear how long this marriage lasted - one account suggests Sarah’s family gave him a million dollars to go away! Within five years of his wife’s death he had married and divorced the widow of a Texas oil millionaire, spent a small fortune, and become a key part of a highly publicized scandal surrounding the death by cocaine overdose of an English silent movie starlet. He died with about $500 to his name in 1919 at age 47.

The beautiful Steinway B was udoubtedly an important part of the musical life of Manoir Denouval in those early years but its owner's health began to fail and changes were coming. Sarah Hershey Brannan Eddy Marsh died in Paris in 1911 at the age of 74 after quite an eventful life. Her sole heir was her daughter Elizabeth (Bessie) Geiger and she became the second owner of both Manor Denouval, and the remarkable Steinway model B.

SECOND OWNER - ELIZABETH (BESSIE) GEIGER

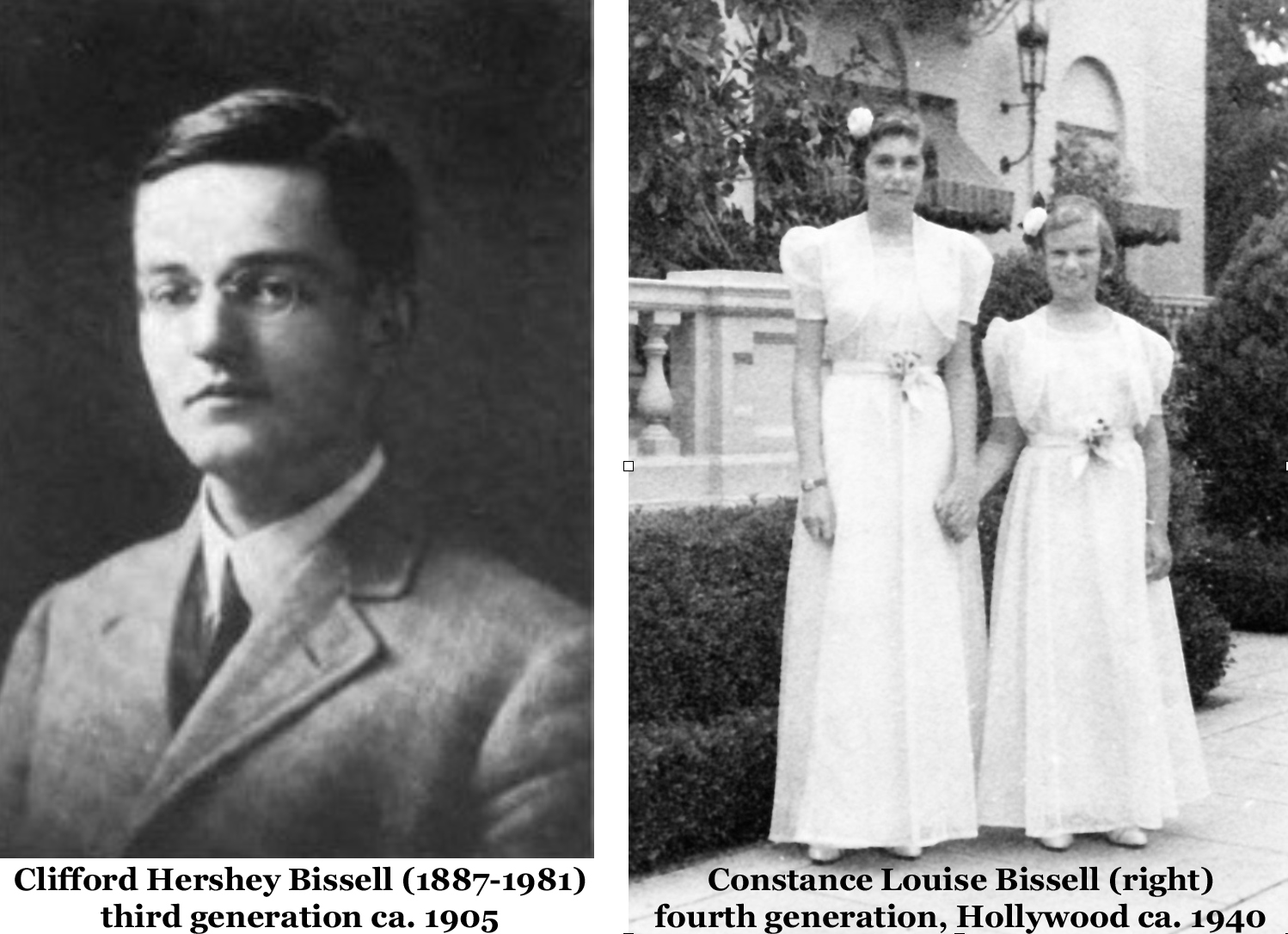

As noted above, Sarah’s daughter Elizabeth McLeod Brannan was born in Iowa in 1861 and may or may not have accompanied her mother to live in Europe when she was a child. It is known that in 1880 at the age of nineteen she married Henry Smith Bissell in Norwalk, Connecticut. Like her mother she married young and her (first) marriage was brief, but it produced three sons, the middle of which, Clifford Hershey Bissell, was born in 1887 and he would decades later, in Berkeley CA, become the third owner of his grandmother’s Steinway model B. Elizabeth’s marriage to Mr. Bissell ended not long after her sons were born and by 1901 when the Steinway was being built she had been married again and widowed, and was living in New York City under her late second husband’s name as Mrs. W. A. Vogel. It was to her home at 327 West 89th St. in New York City that the Steinway was originally delivered while its new home in France was being constructed.

By the time of Sarah Hershey Eddy Marsh’s passing in 1911, Elizabeth (known as Bessie) had married an Englishman many years her junior as her third husband, following somewhat a path taken by her mother. Bessie’s husband’s name was Hector Geiger and he too had a colorful past, but happily they remained married for the rest of Bessie’s long life. Having inherited Manoir Denouval and all of its contents, Bessie and Hector were living very well at Denouval in 1912 and 1913 as documented by extensive photos taken by her son Clifford Bissell, a number of which are reproduced here.

But living a life of culture and comfort in rural France did not remain an option for long. The Great War was on the way and Bessie and Hector left France for England in 1914. England declared war on Germany in August, and In October, with the precious Steinway likely on board in the cargo hold, Bessie and Hector sailed from Liverpool on the Lusitania (famously sunk with great loss of life by a German U-boat the following year) bound for New York. Safe in America, Bessie and Hector headed West, to join Bessie’s son Kenneth and her aunt Mira Hershey (Sarah’s sister), who were all living their own high life - in Hollywood, California.

Bessie sold Manoir Denouval to a wealthy Bolivian in 1915. It went on to have a fascinating life of its own, with many owners and various uses, including as a center for Jewish orphans after WWII, frequented by the likes of Marc Chagall and Josephine Baker. It still stands today. But in 1920 in Southern California plans were underway for a new mansion that would be the Steinway’s next home.

THE NEXT HOME: FRANKLIN AVENUE, HOLLYWOOD CA

Almira (Mira) Hershey, Sarah Hershey Eddy’s sister, had inherited her own huge fortune when her father died in 1893, but while Sarah moved to France, Mira headed West and settled in Southern California, and built herself a mansion in the fashionable Bunker Hill district of Los Angeles around 1900. A few years later she visited the Hotel Hollywood in the Hollywood district and liked it so much she bought it. The movie industry was just beginning and as the years went by this comfortable lodging (renamed the Hollywood Hotel) became the temporary residence of virtually all of the top movie stars and film moguls. Almira invested in land that increased greatly in value, adding to her enormous wealth. By the late teens she was a real estate mogul, rubbing elbows with the film industry’s movers and shakers, and living well. Into this life, escaping from the Great War, came Bessie and Hector Geiger, and the Steinway model B.

Bessie’s son Kenneth had settled near his aunt Mira in a comfortable house on Hillside Ave. in Hollywood. Bessie and Hector rented a house a few blocks away on Hawthorn Ave. and lived there with the Steinway while they began to make plans to construct a suitable mansion. They selected a large lot in the neighborhood on the fashionable corner of Franklin Ave. and Camino Palmero. A local builder’s trade publication announced in September of 1921 that Elizabeth Geiger had engaged the prominent architect Oliver P. Dennis to “erect a two story eighteen room residence of 102 x 68 ft. at 7357 Franklin Ave. having four tiled baths and an automatic water heater at a cost of $40,000.”

The house, which still stands today in a somewhat modified state with a second house covering much of the grounds, was completed in 1922 and as shown was a formidable structure although slightly more modest than Manoir Denouval. The Geigers lived in good company - next door on Franklin Ave. was the great mansion of one of Hollywood’s most successful and wealthiest silent film stars, Anita Stewart. Directly across the street was the home of Samuel Goldwyn of MGM and next door to Goldwyn lived Ozzie and Harriet.

Bessie Geiger was 61 when the big house was constructed, and the Geiger home was the scene of women’s club meetings, poetry readings and musicales but in general the Geigers lived a quiet life. As can be seen clearly when examining the Steinway, piano playing was not a frequent activity, leading to the remarkable condition we find the piano in today.

The Steinway model B remained at the Franklin Ave. house for 25 years until Bessie’s death at age 85 in 1946. It then came north to the San Francisco Bay area, where it lived for the longest period of its life in the Berkeley home of Bessie’s son, Clifford Bissell, who enjoyed a long carreer as a proffesor of French at the University of California. It remained in his Spanish style home on Euclid Ave. until his passing in 1981 when it was inherited by his daughter Constance and moved to her home, also in Berkeley. Having subsequently passed to the fifth generation of the descendants of Sarah Hershey Eddy, it is now offered for sale to begin the next phase of its life with a new caretaker.